Food Sovereignty: Combatting Childhood Obesity in Native American and Black Communities

This blog was written with input from Barb Fabre, CEO, Indigenous Visioning; Trisha Moquino, Co-Founder/Education Director, Keres Children’s Learning Center; A-dae Romero-Briones (Kiowa/Cochiti), Director of Programs, Native Agriculture and Food Systems Initiative; and Gale Spotted Tail, Rosebud Sioux Tribe Child Care Services/Lakota Language Preservation Project.

Every family wants to provide healthy food for their young children. But in the US, systemic discrimination has made this next to impossible. The degree to which families are food secure, i.e., have the “physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life,” often depends on their race and ethnicity. One in four Native Americans experiences food insecurity, compared to one in nine Americans overall. And, in 2020, 24% of Black individuals experienced food insecurity – more than three times the rate of White households. With low access to fresh foods but readily available fast food, childhood obesity has ensued. Native American children have the highest rates of obesity in the US; more than 20 percent of Native American and 14 percent of Black children ages 2 to 5 have obesity, compared to 13.7 percent of US children of all other races. As we know, obesity can put these children at greater risk for diabetes and cardiovascular problems later in life. Before discussing some steps that can be taken to solve the problem, it’s important to acknowledge how we got here.

Deficit Language Disregards History and Hides the Truth

The very terminology used to describe the issue – food insecurity – not only obscures how it came about but places the responsibility on the families experiencing it. But they have not created the situation. Systemic racism and discrimination have led to less access to many goods and services and Native American and Black leaders have not been asked to provide their input on the problem. Instead, the narrative has been shaped by national organizations and federal programs, resulting in the deficit language now in use. Moquino noted:

“National organizations contribute to the erasure of the legacy of Indigenous food sovereignty when they use terms such as “food insecurity,” a term that further marginalizes BIPOC children from their food histories and food systems and does not acknowledge who created these disruptions, unintentionally putting the responsibility back on Indigenous/BIPOC families and communities instead of colonization, the federal government, capitalism, and corporations.”

Romero-Briones said that framing the conversation around “food insecurity” ignores the history that has produced it:

“Food insecurity, or “hunger,” has been the result of a series of racial projects through which Pueblo environmental/land practices have been damaged, management of natural resources and the accompanying wealth have been transferred to non-Indian hands, and the environment has been degraded, [all creating] a dependence on the retail food supply.”

Spotted Tail noted the result of this dependence:

“The US government tactic for taking Indigenous land and sovereignty was to take its food source (buffalo). After being put on reservations and forced to eat government rations, which consisted of beef, government-issued commodities which were high in carbohydrates and starches, obesity and other health problems followed.”

Call It What it Is

Regarding the importance of the words we use to name the issue, Romero-Briones said:

“Pueblo communities are NOT “food deserts.” They are “food retail deserts” and to focus on the lack of retail outlets that “sell” fresh fruits and vegetables places the communities vulnerable to extractive capitalism…the system that extracts the wealth of our land, our people, and systems and creates systems of poverty.”

Fabre indicated that the lack of retail grocery stores within proximity to tribal communities is a very real issue for tribes in Minnesota. Tribal members are eating at fast food places because it is cheaper than fresh foods, and at rural community convenience stores, where there is a lack of fresh fruits, vegetables, and other healthy foods or these items are often double what you would pay in a regular grocery store. Some tribes have Farmers’ Markets; however, those are typically offered one time a month and only during the three to four summer months. In addition, with a very large reservation, it takes some families over an hour to access it.

Small Steps that Could Make a Difference

Many of our food and health policies must be changed. As Romero-Briones noted:

“In the current era of food policy, there are land management policies that prevent tribes from managing their own lands, federal procurement policies that only allow certain vendors to supply food to federal schools (i.e., local producers have a hard time being vendors), nutrition guidelines that are entirely based on western ideas of health and policies, health policies that limit how much access Native mothers have to birthing practices and breastfeeding that influence lifelong health habits and tastes.”

But there is a recent win. In a “first-of-its-kind initiative” for Native Americans, the Food and Nutrition Service allocated $3.5 million to eight tribal nations, granting more autonomy to these communities in carrying out the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations. According to the USDA, it is “fully committed to supporting the restoration of indigenous food, to empower indigenous agricultural economies and to improve indigenous health through traditional foods.”

According to Fabre, the USDA has been quite flexible. Though the onus may be put on tribes to do the asking, traditional foods are easy to fit into its categories of menu items. She spoke about opportunities in the past in which HUD promoted community gardens and deer processing classes to teach younger tribe members the process of growing and consuming indigenous foods. She discussed deer camps for young tribal members that previously had been in place. Other solutions she suggests include:

- Small set asides as incentives for using traditional foods within the USDA food program and Head Start.

- More emphasis from the White House on healthy eating, e.g., a new program akin to Let’s Move, a US public health campaign, led by then-First Lady, Michelle Obama, that aimed to reduce childhood obesity and encourage a healthy lifestyle in children.

- White House conferences on or meetings about the link between childhood obesity, food insecurities, and food sovereignty within tribal communities.

- More collaboration at the federal level between the USDA, HUD, and ACF that increase opportunities for tribal communities to teach about gardens (in housing units), food preservation classes, incentives, etc.

At BUILD, we intend to hold ourselves accountable to the importance of saying it like it is, ensuring we do not use terminology that both veils US history and further marginalizes the populations we seek to support. We appeal here to other national organizations to do the same.

If we change our focus from the short-term, deficiency-focused response that “food insecurity” promotes to the more long-term, self-sustaining approach that food sovereignty demands, we will shift from a mindset that assigns fault to one that is solution oriented. The healthier lives of children depend on it.

Click here or more information on food security vs. food sovereignty.

Biographies

Barbara Fabre is an enrolled member of the White Earth Ojibwe Reservation, MN and has worked for over 30 years at the tribal, state, national and federal levels through committees, advocacy, workgroups, and contracts to support and advocate for tribal and early childhood issues that promote healthy child development for all children. Ms. Fabre’s experience in program development, creating early childhood systems, and promoting collaborations with tribal communities has helped bring new opportunities for Indian Country. Ms. Fabre is founder and CEO of Indigenous Visioning and President of All Nations Rise. She holds a bachelor’s degree in psychology and has received numerous awards for her dedicated work on behalf of children and families.

Barbara Fabre is an enrolled member of the White Earth Ojibwe Reservation, MN and has worked for over 30 years at the tribal, state, national and federal levels through committees, advocacy, workgroups, and contracts to support and advocate for tribal and early childhood issues that promote healthy child development for all children. Ms. Fabre’s experience in program development, creating early childhood systems, and promoting collaborations with tribal communities has helped bring new opportunities for Indian Country. Ms. Fabre is founder and CEO of Indigenous Visioning and President of All Nations Rise. She holds a bachelor’s degree in psychology and has received numerous awards for her dedicated work on behalf of children and families.

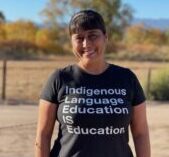

Trisha Moquino is the co-founder of Keres Children’s Learning Center, located in Cochiti Pueblo, a non-profit Keres Language Immersion Montessori school that houses a Keres immersion early childhood classroom and a dual-language (Keres/English) Elementary classroom using Montessori pedagogy. The vision for a school supporting Keres language/cultural learning and academic development came largely from Trisha’s Master’s thesis (2001). The inspiration for acting on the vision was her love for her daughters, her family, her tribes, and her ancestors. For the last four years, Moquino has been working with KCLC colleagues to build the Indigenous Montessori Institute, a teacher training program that uses a philosophy of Indigenous education and the Montessori philosophy, rooted in an anti-racism/anti-bias approach to teacher education reform.

Trisha Moquino is the co-founder of Keres Children’s Learning Center, located in Cochiti Pueblo, a non-profit Keres Language Immersion Montessori school that houses a Keres immersion early childhood classroom and a dual-language (Keres/English) Elementary classroom using Montessori pedagogy. The vision for a school supporting Keres language/cultural learning and academic development came largely from Trisha’s Master’s thesis (2001). The inspiration for acting on the vision was her love for her daughters, her family, her tribes, and her ancestors. For the last four years, Moquino has been working with KCLC colleagues to build the Indigenous Montessori Institute, a teacher training program that uses a philosophy of Indigenous education and the Montessori philosophy, rooted in an anti-racism/anti-bias approach to teacher education reform.

Trisha holds a BA from Stanford University in American Studies and an MA from the University of New Mexico in Bilingual and Elementary Education. Her Montessori Teaching credentials include: AMS (Elementary I), UMA (Early Childhood), AMI (Case de Bambini 2.5 years-6 years). One of the blessings she is grateful for is being able to work with children from her tribe in their Indigenous language of Keres every day.

A-dae Romero-Briones (Kiowa/Cochiti) was born and raised in Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico and comes from the Toyekoyah/Komalty Family from Hog Creek, Oklahoma on the Kiowa side. Mrs. Romero-Briones is Director of Programs-Native food and Agricultural Program for First Nations Development Institute and Co-founder/Director of the California Tribal Fund. She is the former Director of Community Development for Pulama Lana’I and the Co-founder and former Executive Director of a non-profit for Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico. Mrs. Romero-Briones worked for the University of Arkansas’ Indigenous Food and Agricultural Initiative while she was getting her LLM in Food and Agricultural Law. She wrote extensively about food safety and the protection of traditional tribal foods.

A-dae Romero-Briones (Kiowa/Cochiti) was born and raised in Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico and comes from the Toyekoyah/Komalty Family from Hog Creek, Oklahoma on the Kiowa side. Mrs. Romero-Briones is Director of Programs-Native food and Agricultural Program for First Nations Development Institute and Co-founder/Director of the California Tribal Fund. She is the former Director of Community Development for Pulama Lana’I and the Co-founder and former Executive Director of a non-profit for Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico. Mrs. Romero-Briones worked for the University of Arkansas’ Indigenous Food and Agricultural Initiative while she was getting her LLM in Food and Agricultural Law. She wrote extensively about food safety and the protection of traditional tribal foods.

A US Fulbright Scholar, Ms. Romero-Briones received her Bachelor of Arts in Public Policy from Princeton University, a Juris Doctorate from Arizona State University’s College of Law, and an LLM in Food and Agricultural Law from the University of Arkansas. President Obama recognized Ms. Romero-Briones as a White House Champion of Change in Agriculture.

Gale Spotted Tail has been the Child Care Director for the Rosebud Sioux Tribe Child Care Services Program since 1991, and of the Lakota Language Preservation Project since 2014. She has managed three daycare centers, 117 child care provider homes, Lakota song and dance projects, Lakota language revitalization projects, and Lakota cultural programming, and served as chairperson of the National Indian Child Care Association Cultural Committee. She was a Global Leader for the 2016-18 cohort of the Young Children program at the World Forum Foundation.

Gale Spotted Tail has been the Child Care Director for the Rosebud Sioux Tribe Child Care Services Program since 1991, and of the Lakota Language Preservation Project since 2014. She has managed three daycare centers, 117 child care provider homes, Lakota song and dance projects, Lakota language revitalization projects, and Lakota cultural programming, and served as chairperson of the National Indian Child Care Association Cultural Committee. She was a Global Leader for the 2016-18 cohort of the Young Children program at the World Forum Foundation.

Gale has a BA degree in Lakota History and Culture from the Sinte Gleska University and in Park and Recreation Management from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. She participates in Lakota ceremonial events and has had many Lakota mentors during her life’s journey.

Explore More

Stop Talking . . . and Start Walking: Whole Systems That Take Action for Children and Families

Archived Webinar October 21, 2025

Over the course of this Whole Child Whole Family Whole Systems webinar series, we have journeyed together through the many forces that shape the lives of young children and their families: economic stability, maternal health, housing, homelessness, family supports, food security, and environmental conditions.

Pathway to Healing Hubs: A Community Reflection & Action Guide

Planning Tool October 15, 2025

This template is designed to help you co-create a healing hub in your community that centers joy, love, cultural wisdom, and lived experience. Use the space provided to reflect, plan, and dream together.

Hungry for Change: Tackling Food Insecurity and Nutrition Through Systems That Work

Archived Webinar September 22, 2025